“I was 17 years-old when I got married to my husband. He was 19 and he earned 37 and a half cents per hour. His best friend moved to California and talked us into coming down because he could earn more money. I was a typical housewife and never expected to work outside the home. I knew he was a good provider. And, so it was, with what little we had, we were doing fine. We moved and he got a job as a roofer.

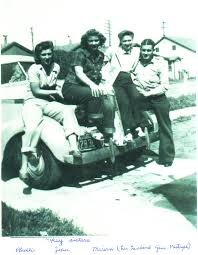

By then, the shipyards were starting and we always went for a Sunday drive. This one time we went, we took another couple with us and the guys were talking and they decided they wanted to learn to weld and get jobs in shipyards. By then, I had a baby. I’m in the back seat with the other woman and I piped up and said, “me too,” even though I really didn’t even know what a welder was.

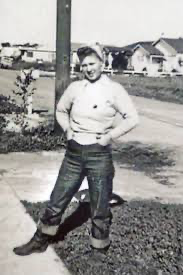

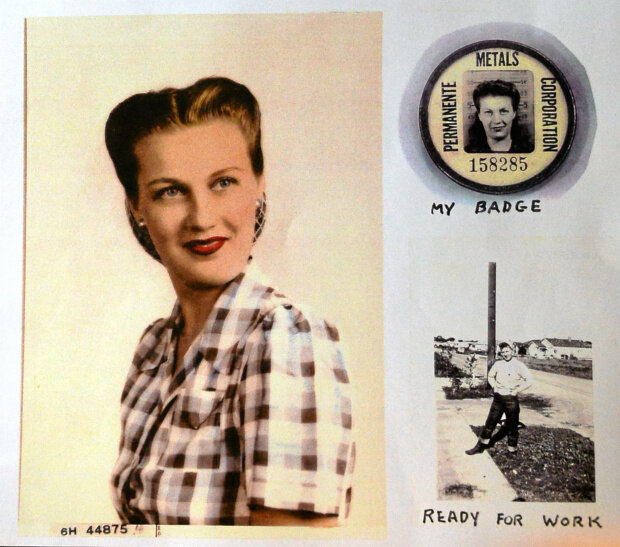

My husband learned to weld, got a job in the shipyards and we bought a house in Richmond. I kept thinking about, “you know, maybe I would like to work there.” My family was still in Oregon, and I talked one of my sisters into coming down to take care of my little boy. I went to the employment office and got my social security card and at the local high school, they had a welding class that went 24 hours a day. They assigned me 4-8am and I was not an early riser.

I didn’t drive, either. I can’t remember exactly how far it was from where we lived to the high school, but it was quite a distance. I had to get up in the middle of the night and walk there. After two weeks, they said I was a welder. I could go into Oakland, to the hiring hall and get a job. When I got there, they wouldn’t hire me. They told me I had to belong to the Boilermakers Union. I went to the Boilermakers Union and they told me they didn’t take women or blacks.

I kept going back to the hiring hall. They’d say no. One time I just started crying. I just was so frustrated. There was a man at a table in the back of the room. He asked me what was wrong and when I told him he said, “Go back up there.” I went back one final time and they hired me.

They hired a total of six women. And we knew we had a job, but we couldn’t do the job until the Boilermakers gave in. Finally in July of 1942, the Boilermakers caved and the shipyard hired a chaperone to bring the six of us out to them. They had no idea what the men would do when we’d got there. It worked out fine. I’m sure they thought we were weird because that was, you know, that was an all-man place. And here we were, dressed in leather coveralls, a leather jacket and we had our leather gloves that came up to our elbow. We looked pretty freaky. There were no women’s work clothes. I wore Levis, men’s boots, and sweatshirts that came in one color only. It was so noisy and busy. They assigned me to work with a ship fitter. And the first thing that I welded was a clamp onto a big sheet of sheet metal.

I was on a crew of fifteen men. I was the only woman.

Every morning, the overseer would assign different things that needed to be done. The guys always got the best of it and I’d be left with what I called it the ‘ticky-tacky’ stuff. One morning I thought, “you know, some of those guys don’t have any more training that I do.” I walked right in lockstep behind my lead man, and every time he’d point to something, I’d say, “ I can do that!” Finally he said, “Well, do it!” From that point on I was part of the crew and I was treated fairly equal.

My husband was a journeyman welder by then. I started work at 90 cents an hour. After a certain time we got a raise. The next step was to become a journeyman welder.

I achieved that and here I was doing the same work my husband was and getting the same pay for it. My husband couldn’t handle that because in those days, the man was the head of the house and my husband couldn’t accept that he wasn’t. I was buying things that I’d never even been allowed to have before. Because prior to this, he never allowed me to have any money in my hand and I couldn’t buy anything just for me. That was common.

Only in later years did I understood that his whole being—his pride—was in how he could support his family. I had basically taken that away from him. I was buying Frank Sinatra records, goofy hats and fancy underwear.

For Christmas that last year, he bought me pots and pans.

There was always the pressure to quit, you know, he wanted me to quit, and sometimes I’d say “Ok, I will,” but then I didn’t. So, he left me. He went over to Pearl Harbor to do repairs on ships that had been bombed.

My sister Marge became a welder. Then, my mom said she wanted to get in on it too so she did. She went to the hiring hall dressed as she always did, you know, with a suit and gloves and the whole business. They said, “Lady, I don’t think you want to do this.” We got her into some coveralls and send her down there again and they hired her.

As they closed down the shipyard and stuff, she kept working right to the very end. I ended up marrying a guy I met at the shipyard. By the end of the war, I went back to being a housewife with the dress and the apron. My sister explained it the best, I thought.

She said, “The guys signed on for a hitch in the military and we signed on for a hitch to help ‘em.

Most of us never expected to work outside the home and se went back to being housewives. I had four more kids. We just went along because everyone was involved in helping with the war effort. It wasn’t anything special in our minds. It wasn’t until 1995, that the idea of women workers got some attention until the Richmond city councilwoman brought it to light. When she was running for reelection, she was going door to door in Richmond and she found there were a lot of women who’d worked in the shipyards. She put a thing in the paper for them to write to her and, that maybe we could get together and have some sort of acknowledgment of what we’d done. It just exploded. So many women came forward and some other women caught onto the idea and it took us only five years to get our national park.”